Saturday, January 31, 2015

Zion

As a general rule, I will not enter Zion. But, today, VSO had sort of an idea of a place we could go. We got up and out of the valley, into a canyon that is not necessarily on the tourist track. It was a pretty nice little eight mile round-tripper. Here she is on the way down.

Friday, January 30, 2015

After the Epilogue

As my reader knows, I spent some time earlier in the year analyzing a bunch of trash data collected from the ditches around Parowan. One of the topics I addressed during that analysis was something I termed the Buzz Price. On that particular topic, I reached the conclusion that the best buzz price available in southern Utah was found in a shampoo bottle full of rotgut hard liquor. In other words, bottom shelf vodka provides the best bang for your buck. I know that at least one commenter feels that I need to move on, and stop being distracted by alcohol related trash. But, I feel compelled to relate that I took my researches to Beaver, Utah—the next town north of Parowan. I visited the liquor agency there and had a chat with the owner. (She is always friendly, and probably sees me a little too often.) I asked her to name her biggest seller. Without even a split second of hesitation she said, "Cheap vodka." I am not kidding. I asked her, "You mean the stuff on the bottom shelf in the plastic shampoo bottle?" "Yeah, I sell more than 30 cases per month." I almost fell on the floor. Cases?! In Beaver, Utah?! "Yeah," she said, "most people buy it by the case."

Friday, January 23, 2015

Another Technology Passes Us By

We were somewhere on the north side of Mt. Terrill yesterday. We were doing some off-trail training on the snow machines. I've putted around on snow mobiles a fair number of times before. But, like most outdoor sports, the technology and the terrain have been pushed to the limits, leaving me to appear incompetent in front of my peers. In fact, one of my colleagues tried to teach me to steer the machine by leaning the track from side to side. He insisted that I should not need to use the skis for turning, but should be able to do it by leaning. I'm sure he is correct—and the proof is in the picture—but I couldn't master it. Needless to say, I flunked the training.

Tuesday, January 20, 2015

Epilogue

I'm going to begin

this post with a recap. We started this

series with a description of a data collection project that we conducted on the

outskirts of Parowan. Specifically, we

counted aluminum cans dumped in the ditch along 1.5 mile segments of two area

roads. Along with those data, we

recorded the availability and pricing of mass-market suitcase beer in Parowan. Putting those two bits of information

together eventually lead us to a consideration of the economics of drinking

behavior, which lead us further to consider why some of the behavior seems

irrational, at least from a cost and calorie standpoint. This post is going to be a speculation on

irrational behavior. Nothing in this

post has been proven. This is

conjecture.

Before we begin, let us list our assumptions. These assumptions have been generated by our consideration of the data. Nonetheless, we do not consider them "proved." In other words, we think they are justified, but we are aware that our sampling design, including the lack of a control as well as missing information about, among other things, traffic volume, leaves us without proof.

Is any of the foregoing true? Honestly, we don't know. But, we think it might partially account for the high volume of can trash around Parowan. Do we care? In other words, do we have a moral problem with people maybe drinking a little beer on the down low? Absolutely not. About the only criticism that we might have at the end of this whole experiment is that we don't like trash, and this particular behavior creates a lot of trash.

Before we begin, let us list our assumptions. These assumptions have been generated by our consideration of the data. Nonetheless, we do not consider them "proved." In other words, we think they are justified, but we are aware that our sampling design, including the lack of a control as well as missing information about, among other things, traffic volume, leaves us without proof.

*The presence of 899

aluminum cans along three miles of road that we surveyed in the Parowan Valley

is an extraordinary amount of trash, especially when we consider that Rural

Ways has collected several hundred cans for recycling along both segments in the

past two years. Put simply, our first

assumption is that the amount of can trash is more than normal, more than what

we should expect. (Granted, we have not

sampled in Kentucky or Tennessee, so we could be wrong—and those who have ever

lived in or visited those two states will know what I mean.)

*The cans that we

counted were from drinks purchased locally.

Specifically, there are two places to buy suitcase beer in Parowan. And we believe that most, if not all, of the

beer can trash is being generated by purchases at these two locations.

*Drinkers of

mass-market suitcase beer, despite its low alcohol content in Utah, are

drinking it for the effect. That is, we

do not believe that buyers of 18 can suitcases of Natty Light are drinking it

for the excellent flavor. We believe

that most of our beer drinkers and beer can tossers are engaged in the pursuit

of buzz.

Given these

assumptions, and the rest of the data we have presented, the question remains,

what is going on? Our best guess is that

these data demonstrate that there are some closet drinkers in the area. In other words, someone is buying, drinking,

and tossing beer cans so as not to get caught consuming alcohol. This is drinking that is designed to be

hidden from someone. Well. Like.

From whom? The easiest answer is

parents. I mean, what high school senior

has not spent an evening sneaking around with the gang trying to drink a

six-pack undetected? (Please do not let

my daughter read this post.) Part of the

Parowan area can trash is undoubtedly underage drinking. But does that explain it all? Again, without a control, it is tough to say,

but we think there is more trash than a couple of wild high-schoolers can be

dumping—especially because this is a small town where everybody knows

everybody and it is not legal for high-schoolers to buy it. Dare we say it? We think that the position of the church

regarding the consumption of alcohol may be pushing otherwise legal drinking

underground. There. In this case, the "church" is the

LDS church. (Full disclosure: Nearly all of our neighbors and friends are

LDS. We have a lot of respect for the

LDS community and believe that LDS people make the best friends and neighbors

in the world. So, this is by no means an

attack on anything LDS.) If someone with

a Mormon affiliation of some kind, either through blood or marriage, is

interested in having a little drink on the side, how is he or she going to do

it? He can't go to the liquor agency—it

sits directly in the middle of town between the city office and the bank. He is going to stop at the TA to buy

gasoline—nothing wrong with that—and quickly slip a suitcase of the Beast

into his truck. He is going to drive a

lonely country road with the window down, chugging half the suitcase and

tossing all the evidence out the window.

He is going to stop at the end of the road and put the remaining six

cans in his work cooler, at the bottom under the Mountain Dew. He is going to chew a bunch of gum for the

rest of his commute. He is going to arrive

home for dinner, where some member of the domestic community would not

appreciate the consumption of alcohol, with a bit of a buzz. He is going to say little, do a few chores,

and fall asleep early.

Is any of the foregoing true? Honestly, we don't know. But, we think it might partially account for the high volume of can trash around Parowan. Do we care? In other words, do we have a moral problem with people maybe drinking a little beer on the down low? Absolutely not. About the only criticism that we might have at the end of this whole experiment is that we don't like trash, and this particular behavior creates a lot of trash.

Monday, January 19, 2015

Buzz Price

|

Vendor

|

Item

|

Per Can Cost

|

Buzz Price

|

Annual

|

|

Maverik

|

18 Can

Natty Light

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.56

|

$ 2.80

|

$ 1,022.00

|

|

Maverik

|

12 Can

Natty Light

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.58

|

$ 2.90

|

$ 1,058.50

|

|

Maverik

|

30 Can

Natty Light

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.60

|

$ 3.00

|

$ 1,095.00

|

|

Maverik

|

12 Can

Beast

|

$ 0.62

|

$ 3.10

|

$ 1,131.50

|

|

TA

|

12 Can

Beast

|

$ 0.67

|

$ 3.35

|

$ 1,222.75

|

|

Maverik

|

30 Can

Budweiser

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.67

|

$ 3.35

|

$ 1,222.75

|

|

Maverik

|

18 Can

Budweiser

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.72

|

$ 3.60

|

$ 1,314.00

|

|

Maverik

|

12 Can

Budweiser

or

Equivalent

|

$ 0.75

|

$ 3.75

|

$ 1,368.75

|

|

TA

|

12 Can

Keystone Light

|

$ 0.86

|

$ 4.30

|

$ 1,569.50

|

|

TA

|

12 Can

Coors Light

|

$ 1.13

|

$ 5.65

|

$ 2,062.25

|

|

TA

|

12 Can

Budweiser

or

Equivalent

|

$ 1.16

|

$ 5.80

|

$ 2,117.00

|

In the past few

posts we've presented a fair amount of data from our trash collection

experiments in the Parowan Valley. At

this point, we are prepared to hazard a couple of tentative conclusions. As we mentioned in the prologue these

conclusions may reveal things about personal behavior. We realize that our reader may disagree or

disapprove. At the risk of alienating

our already tiny audience, we are going to go ahead and highlight two

points. The first, what we call the Buzz

Price, will be discussed here. The

second, which is our speculation about the reasons for beer can tossing, will

come in a subsequent post.

Without further

comment, let's jump right in to an interesting topic. Why do people drink alcoholic beverages? Clearly, there are numerous reasons,

including taste, status, peer pressure, etc.

But, the number one reason has got to be the effect. Can anyone seriously disagree? People drink alcohol for the buzz. If that is true, which we think it is, why is

so much 3.2% beer consumed in Utah? If

you want a buzz, there is more buzz per mouthful in a glass of wine or a shot

of whiskey. Thinking about this question

lead us to come up with a measure of buzz per buck—the buzz price. Is it cost effective to look for buzz in 3.2%

beer? If not, why not?

We start with a

couple assumptions. First, the average

person will be buzzed from three drinks.

While we understand that to get a large person really hopped up might

take six or eight, we're going to stick with three. This is partly due to a lot of personal

experience, but also because it seems to be the standard for bartenders and

regulators. Three drinks is generally

understood to equal 1.8 ounces of alcohol (.6 ounces per drink). In Utah, where convenience store beer cannot

contain more than 3.2% alcohol, it takes five drinks, or five cans of beer to

reach 1.8 ounces of alcohol. (The number

is actually 4.7 cans, but we rounded up.)

We're not going to show all our math, but you can quickly see that it

becomes a straightforward calculation.

Convenience store beer buzz prices are ranked above. (Natty Light equivalents are Keystone Light,

Busch Light, and Busch. The annual cost

is for 365 daily buzzes.)

To get your buzz on

for under three dollars a day seems like a pretty good deal. But there might be a couple of other things

to consider. First, what is the cost of

your other options? And, second, what

does it do to your waist line? The

answer to the first question is that you can do better elsewhere. You can, in fact, drink wine—not plonk—for

about the price of Natty Light and for far less than Budweiser. I don't mind the red wines sold in the BOTA

box—malbec, zinfandel, shiraz. Like I

say, they're not for real wine people probably, but they are at least one cut

better than plonk. (For plonk, you could

certainly pay less.) But let's stop

fooling around. If you want the best

buzz price you should be looking at hard liquor in a shampoo bottle. Go to the state liquor agency. Go to the back. Go to the bottom shelf. And take the plastic bottle. The label doesn't matter. Whatever is in it will make you gag. (Or so I have heard.) But you will be paying something less than a

dollar for your buzz. So, what about the

answer to the second question? How many

wasted calories are being consumed in pursuit of the buzz. I suspect that my reader may have guessed the

outcome. Light beer is something of an

improvement, but you're clearly going to minimize the beer gut if you switch to

vodka.

|

Vendor

|

Item

|

Buzz

Price

|

Annual

|

Buzz

Calories

|

|

Liquor

Store

|

Plastic

Bottle of Popov Vodka

|

$

0.91

|

$ 332.15

|

291

|

|

Maverik

|

18 Can

Natty Light or Equivalent

|

$

2.80

|

$

1,022.00

|

475

|

|

Liquor

Store

|

4

Bottle BOTA Box of Wine

|

$

2.82

|

$

1,029.41

|

366

|

|

TA

|

12 Can

Budweiser or Equivalent

|

$

5.80

|

$

2,117.00

|

725

|

If you can spend

less and consume fewer wasted calories by drinking wine or spirits, why would

you drink convenience store beer? Maybe

beer drinkers truly prefer beer? I mean,

I can understand that. I am very fond of

brown ale. A Newcastle or a Moose Drool

will keep me coming back (up to three times).

But we're talking about tasteless, over-carbonated, ah, stuff. Is anyone really drinking it because they

like it? OK. I'll admit rotgut liquor is hard to like,

too. Or so I've heard. Be we suspect that there might be something

else going on, and will post about it shortly.

Sunday, January 18, 2015

Data Collection Site 2

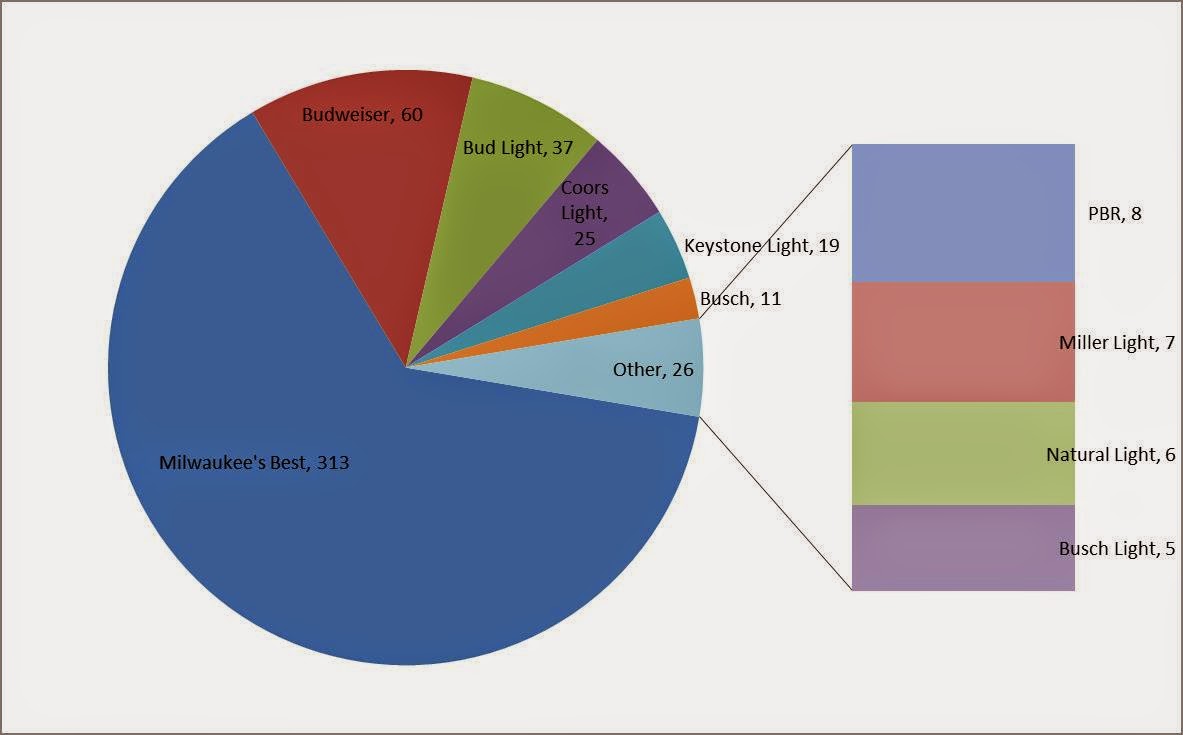

Any serious student of can trash will

quickly begin using the terms "can density" and "can

diversity." While our first can

sampling site had very high can density, our second site was notable for its

can diversity. At our second site, we

identified 36 different species of can.

More importantly, however, there were fully 10 different brands of can

for which we recorded at least 10 cans.

Given this diversity our reader will probably not be surprised to hear

that there were some surprises in the data.

But before getting into the details, let's look at the totals and divide

things up by genera: We counted 278 beer

cans, 65 caffeine cans, and 10 fruit cans, for a total of 344 cans.

Starting with the largest data category, we

counted 18 species of beer, two more than at our other site. Half of them did not qualify as

"important" (at least five cans).

These were Icehouse, Michelob Ultra, PBR, Miller Lite, Coors, Steel

Reserve 211, Modelo, Miller High Life, and Redds Strawberry Ale. The other nine made our pie chart. And this is where the surprises begin. At our first site, Milwaukee's Best made up

almost 60% of the trash; at this site, it was barely 6%. (I immediately drove to the local convenience

store—the Maverik—and found that a 12 can suitcase of the Beast was

$7.49. Ah-ha. That is less than you'd pay at the TA, but

more than you'd pay for Natty Light at the Maverik.) But what really stands out is the Fosters

Lager. Out of nowhere it jumps to 9% of

the beer trash. And with no

suitcases. You may buy Fosters at the

convenience store. But only by the

can. You can buy one can at a time. And it costs more than $2.50 per can. The cans are large, but still . . . this is

one of the mysteries of our study and one which cries out for further research.

Moving on to the other families, you'll

notice that the non-beer population is slightly more important at this site

than it was in our earlier data set. The

caffeine and fruit categories combined make up nearly 20% of our data from this

site, but that is partly because there are fewer cans overall. Perhaps a better way to compare sites is to

look at another metric: trash/linear

foot. At our first site, there was a

non-beer aluminum can every 152 feet; at our second site, that dumping rate had

increased to one can for every 120 feet of road. The other surprise here was that Pepsi and

Mountain Dew switched places. At our

first site, Mountain Dew lead the caffeine family by a fairly wide margin over

the number two choice, Pepsi. At the

second site, Pepsi was on top, with Mountain Dew falling to third. This battle between Pepsi and Mountain Dew,

though, really was the story of the caffeine data—at least from our small data

set. Red Bull made a showing, and there

was some Monster out there, but Mountain Dew and Pepsi are truly fighting for

the hearts and minds of the local caffeine can tossers.

Now that we've discussed a little of the

raw data from our second can counting location, the question quickly becomes

one of beer economics. What does a beer

suitcase cost at the local seller, the Maverik?

And this is where things become very interesting. Have you ever been inside the Maverik? Half of the shop is taken up with beer

suitcases. I'm serious. The variety of styles, sizes, and prices is

boggling. Right away this may explain

the increase in can diversity at the local dump site. I'm not saying that mass-market beer drinkers

are too stupid to pick the best deal, but I am saying that I'm too stupid to do

it. There were at least seven different

price points. I had to put it all in a

spreadsheet.

(When I went to the local Maverik to gather

my price data I stood for a long time in front of the beer cooler. Several people came and went. Eventually I was standing there with a

friendly young guy, covered in tattoos.

He said, "Choices, choices."

I am not kidding. We switched

places a couple of times. He was trying

to decide what to buy. I was

pretending. Eventually we got to

talking. He'd worked for a time in

California. "Out there you can get

all kinds of beer. When I came back to

Utah, I had to switch to whiskey. Beer

is just my chaser now." He

laughed. "What you can do—with a

beer bottle—is to drink the beer down to the bottom of the neck and then fill

the neck with a shot of fireball whiskey.

It's awesome. I can only do three

or four of those in a row though."

We stepped past each other again.

"Hey," he said, "I guess I'll go with the Busch

today." He picked an 18 can

suitcase for $9.99. Smart. Very smart.

Smarter than me. By a lot. I was still standing there trying to figure

out how to do the math.)

12 Can

Suitcase

|

Cost/Can

|

18 Can

Suitcase

|

Cost/Can

|

30 Can

Suitcase

|

Cost/Can

|

|

Natural

Light

|

6.99

|

0.58

|

9.99

|

0.56

|

17.99

|

0.60

|

Keystone

Light

|

6.99

|

0.58

|

9.99

|

0.56

|

17.99

|

0.60

|

Busch

Light

|

6.99

|

0.58

|

9.99

|

0.56

|

17.99

|

0.60

|

Busch

|

6.99

|

0.58

|

9.99

|

0.56

|

17.99

|

0.60

|

Bud

Light

|

8.99

|

0.75

|

12.99

|

0.72

|

19.99

|

0.67

|

Coors

Light

|

8.99

|

0.75

|

12.99

|

0.72

|

19.99

|

0.67

|

Budweiser

|

8.99

|

0.75

|

12.99

|

0.72

|

19.99

|

0.67

|

Milwaukee's

Best

|

7.49

|

0.62

|

none

|

none

|

The spreadsheet results (above) start to tell the story. They certainly explain, for example, the rise of Natty Light and Keystone Light at this data collection site. The two combine for almost 100 cans, or almost a third of the trash. It is, however, more difficult to tell what is going on with the Busch Brothers. Given the price, it is hard to explain why they are languishing in the polls. (Again, we admit to some missing pieces of information: Perhaps Busch drinkers simply don't throw their cans in the ditch?) The positions occupied by Bud and Bud Light correspond to what we found at the TA. That is, those brands seem to be in a position to charge something of a premium among mass-market beer drinkers—without giving up a lot of sales volume. They evidently hold a good market position. In contrast to our first site, Coors Light, with a similar strategy, is doing a little better here. Sort of holding its own. But overall it doesn't have quite the selling power of the Buds. Finally, while we find these data somewhat inconclusive, the distance of dumping from point of purchase is quite a bit different at this site. Most of the cans go out at the one mile mark. But this actually 2.5 miles from the point of sale. (See the map in the prologue.) Are Maverik beer buyers slower drinkers than those who frequent the TA?

Saturday, January 17, 2015

Data Collection Site 1

Let's start with

some headline numbers, some eye-popping numbers. In the 1.5 mile stretch from the northern

edge of town near the TA to the first 4-way stop in the Parowan Valley (see map

in Prologue), we recorded 555 aluminum cans in the ditch. My reader may not feel that this is any big

deal, but it seems like a lot to me.

Moreover, I walked a portion of this road myself about two years ago and

collected a hundred cans for recycling.

So, I know for certain that these new numbers underestimate the true

volume of trash. But, even at the rate

of 555, that equals one can every 14 feet.

We divided the

census data into three families: Beer,

Caffeine, and Fruit. While everyone

knows (and loves) beer, the latter pair of groupings can sometimes be difficult

to distinguish. For example, what is

"MUG Root Beer?" Is it

caffeine or fruit? I don't know. I don't know if it has caffeine. If it doesn't have caffeine, it should be

typed as "fruit," by which we mean non-caffeinated sweet drinks. Ultimately, though, it doesn't matter a lot

because these categories—especially fruit—turned out to play only a minor

role in our data collection. In fact, at

this site only seven of the 555 cans were finally classified as "fruit,"

or just a shade over 1% of the roadside trash.

Either fruit drinkers are not very trashy, or they are not very

common. As for caffeine, the numbers

were quite a bit larger, but still made up only a small percentage of the total

(around 8%). Just to provide a feel for

what kind of caffeine is being consumed (and ditched) in the Parowan Valley,

the top three vote-getters were Mountain Dew (16 cans), Pepsi (9 cans), and

Monster (5 cans). No other caffeinated

drink scored even five votes.

So, if the Caffeine

and Fruit families account for just nine percent of the can trash at our first

data collection site, what does that say about Beer? Wow.

We counted 503 beer cans in 1.5 miles, or one every 16 feet. In addition, there were 16 different species

of beer. Which is to say that we

identified 16 different labels. Of

these, we decided that six of them were of low importance—occurring fewer than

four times each. These were Milwaukee's

Best Ice, Coors, Hurricane Malt Liquor, Bud Ice, Pacific Western Traditional

Lager, and Icehouse. The ten remaining

beer species—shown in the pie chart—accounted for 88% of our data, so we

began to concentrate our trash analysis on these brands of beer and their drinkers.

After taking a quick

look at these data, we immediately wanted to know what was being sold, and for

how much, at the TA truck stop nearby.

It is axiomatic that correlation is not causation, so we're not saying

this proves anything, but the truck stop sells just five brands of suitcase

beer. (I don't want to spend a lot of

time on this, but we have become somewhat convinced that this particular type

of can traffic is associated with beer that you buy in a cardboard

suitcase.) These are Milwaukee's Best,

Budweiser, Bud Light, Coors Light, and Keystone Light. Well.

Are people driving 54 miles—the distance between Beaver and Cedar City,

the only other two sources of beer—to buy Milwaukee's Best, drink it, and

throw the can in the Parowan Valley? We

think not. But, before we begin

speculating on behavior, let's discuss cost.

For a 12 can suitcase at the TA Milwaukee's Best costs $7.99 ($.67/can);

Bud and Bud Light go for 13.89 ($1.16/can); Coors Light is $13.59 ($1.14/can);

and Keystone Light is $10.29 ($.89/can).

Let me save the

worst of the speculation for the portion of this paper that comes after all the

data have been presented. For now, let

me offer a few observations:

*Despite the name,

Milwaukee's Best is not famous for stimulating the palate. As a much younger man I remember drinking it

for certain other reasons. In fact, for

a while the brand was widely known as "The Beast," referring I

presume to how I looked the next morning.

*All of the beer

sold in suitcases at truck stops in Utah has an alcohol content of 3.2%. All of it.

So, you can't charge more for a higher alcohol content like you might

elsewhere. Despite this fact,

Anheuser-Busch, with its two brands—Bud and Bud Light—is selling quite a bit

of beer at almost double the per can cost of Miller-SAB's

"Best." Is Budweiser really

worth twice as much? Of all the money

spent on beer in this sample, Anheuser is collecting 30% of it. How are they doing that with beer that is

hard to distinguish from, um, other yellowish liquids? Actually, I have no idea. I wonder if it is the marketing? I mean, from what I hear, the Super Bowl is

trying to buy television time to run advertisements during the Bud Bowl.

*The pricing

strategy of the third big brewer—Molson Coors—doesn't make sense to me. At least at this location, it seems to be a

failed strategy. They are not really

competitive at the high end, where their pricing is similar to Anheuser. (Although, remember, this is

speculative. Coors Light may be selling

very well. But Silver Bullet drinkers

may not be can tossers, which would clearly impact our conclusions.) But, they are really struggling at the low

end, where the price point of $10.29 for a suitcase of Keystone Light is almost

incomprehensible. It is not cheap enough

for the cost conscious and not expensive enough for the status conscious.

Friday, January 16, 2015

Prologue

As some may know, we have always had a bit of interest in trash here at Rural Ways. We often scour the highways and byways for something useful and sometimes make a little money by recycling metals. Recently, however, there has been an explosion of interest in trash at The Homestead due to the preliminary results of some scientific trash sampling in the Parowan Valley.

(DISCLAIMER: Before beginning any

discussion of trash, however, I think it is only fair to warn my reader

about two problems. First, while many may not know this, trash data—and

the conclusions to be drawn from them—may be divisive and controversial.

It is difficult to discuss trash without discussing people and what they

do. So, if you are unprepared for Rural Ways to delve into issues of

human evil—namely, beer and capitalism—you might better jump ahead to safer

topics such as tree identification and house painting. Second, despite

our best efforts to design sampling protocols in such a way as to avoid

spurious and biased conclusions, a number of data collection issues may become

increasingly obvious as we publish our preliminary results. It is, for

example, difficult to identify trash after it has been through a rotary mower.

Because our sampling locations have been mowed at different frequencies, the

results from one area may not be comparable to the results from another.

One way to control for this particular problem is to select trash that is less

likely to be obliterated by a mower. And, in this case, that is exactly

what we have done. So, if we are ready to move on from the

legal small print and into the topic itself, I will begin by stating that we

collected just one kind of trash: cans. These data and the conclusions

we draw from them are from aluminum can trash.)

What did we count? We counted cans along the road, from the edge

of the pavement to the edge of the right-of-way—basically we were surveying

drive-by trash, trash in the ditch, trash out the window. For every quarter mile we did a 100% can

count by species on both sides of the road.

We did this for six road segments—each 1/4 mile in length—from mile

zero to mile 1.5.

Where did we count? We started with two hypotheses. First, we assumed that only the most

obnoxious trash tossers—and believe me there are definitely some trashy people

out there—would jettison the can immediately into the driveway or front

yard. So we wanted to start our counts

exactly on the edge of town, just past the last house. Second, we assumed that beer cans would make

up an interesting segment of our data and we wanted to be in a position to

count them. With the exception of the

state liquor agency—where microbrews can be purchased at $3 per can—there are

just two places to buy beer between Cedar City and Beaver, a distance of 54

miles. So, we wanted to begin our counts

along sections of road that were directly accessible to these two vendors. Based on this pair of hypotheses, we chose to

start counting cans at two locations.

The first was on the north side of town on a paved county road starting

almost adjacent to the TA truck stop (one of the beer sellers). The second was along old Highway 91—the

former road to Las Vegas before the interstate was constructed. This highway leads directly away from the

second beer vendor, Maverik—which is exactly 1.5 miles from the edge of town

and the start of our data collection.

Sunday, January 11, 2015

Rehabbing

At the end of December I was walking a lot. On some days it was up to eight or nine miles. My left knee started to get sore. But there was a lot to see, so I kept walking. Eventually the knee was very sore. Not unstable or acutely sore, but chronically, wear-and-tear sore. I needed to do something for it. So I took a couple of days off, gave it a blast of ibuprofen—up to 1600 milligrams per day—and started rehabbing it. It has worked out pretty well. My goal is to keep it to about two miles per day. I'm more or less on target, but sometimes it isn't the mileage that matters. On Friday I probably overdid it. I wanted to get up on a little ridge above town. It wasn't a lot more than two miles but it was pretty steep ground. I found myself 1200 feet above the Chev: Climbing down was pretty hard on both knees.

Tuesday, January 6, 2015

Hovenweep

Last Friday much of the Four Corners area was blanketed in an icy fog. It was five degrees fahrenheit. It wasn't the best day for painting, or even hiking the canyons, so we went to Hovenweep. The new snow and low light made for good pictures—highlighting the ruins. We completed the entire circuit at the main part of the monument and then went out to Cutthroat Castle. The castle was a little higher up the mesa. It was sunny there: The pictures were less interesting, but the structure itself was unique. On the way out, the Chev—running on bald tires—failed to clear a couple of steep sections on the road. I had to shovel my way to the top.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)